🟧 96 Units On Ocean // Balboa Reservoir Project Update

In this week’s newsletter, we dig into plans for 96 units of housing on Ocean Avenue and more.

On Nov. 14, 1931, the residents of the neighborhoods and winding enclaves West of Twin Peaks welcomed the El Rey Theater with open arms.

Sunday, Nov. 14, 2021 marks the 90 years since the former El Rey theater opened for its first screening. To mark the occasion, the Ingleside Light is republishing Therese Poletti’s article for the Art Deco building’s 80th anniversary. —Alex Mullaney, editor and publisher

When a big, luxurious movie palace opened on Ocean Avenue in November, 1931 — still early in the Great Depression — the green and red neon glow from its striking 146-foot Art Deco tower made it seem as if Christmas had arrived early.

The residents of the neighborhoods and winding enclaves West of Twin Peaks welcomed the $500,000 El Rey Theater with open arms.

“To me, it seemed like a neighborhood Fox Theater,” said Frank Grant, 86, a native San Franciscan now living in Hillsboro, Ore., referring to the now-demolished San Francisco Fox on Market Street. He and his younger brother Charles would often go to the El Rey from the Parkside. “It was a great escape from the worries of the day.”

True to its name, the El Rey was indeed a king of neigh- borhood movie houses, with seats for about 1800, an especially ambitious venture as the economy hit the skids after the Crash of ‘29. When the El Rey Theater opened on Saturday night, November 14, 1931, its towering presence was meant to anchor a burgeoning retail pocket of Ocean Avenue. After closing as a movie theater in 1977 during a dark decade of urban change, the now salmon-colored building still stands today, rescued by the Voice of Pentecost 34 years ago, and avoiding the fate of other shuttered, single-screen theaters.

Its name perhaps is indicative of the chutzpah of its original owner, local theater operator Samuel H. Levin, who decided to build the theater on the then-untapped commercial block of Ocean Avenue. In November, 1928, Levin first contacted local architect Timothy Pflueger about building a neighborhood the- ater in Mount Davidson Manor, across Ocean Avenue from the young Ingleside Terraces subdivision, built on the site of a former race track. A month later, he changed his mind and asked Pflueger to put his plans on hold, perhaps realizing that a commercial district needed to be more built up before he went forward.

“Levin in, says he has made some definite decisions, i.e. not to build a theater now, to build only stores,” Pflueger wrote in his office datebooks in 1928. Pflueger, a native who grew up in the Mission District, was becoming a well-known architect during the building boom of the Roaring Twenties. His firm, Miller & Pflueger had designed the city’s first high-rise skyscraper, the Telephone Building, and two local neighborhood theaters, the Castro and the Alhambra on Polk Street. Two other theaters, the Senator in Chico and the State in Oroville, more Moderne in design, had just opened several months before Levin called. In the late 1930s, Pflueger would also design the first main building at City College of San Francisco, among the many works in the firm’s vast portfolio.

In the 1920s, West of Twin Peaks was growing as an affordable bedroom community. Suburban residential parks were carved out by savvy real estate developers, in anticipation of the opening of the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1918. Beginning in 1911, the vast acreage south of Mount Davidson once owned by Adolf Sutro was sold and parceled off. Developers began mapping out separate, charming “residence parks” that exist today.

But the commercial district of Ocean Avenue where the El Rey stands was slower to develop, perhaps tainted by its earliest associations with drinking and betting. Previously known as Ocean House Road, or Old Ocean Road, in the mid-1890s, a special Southern Pacific train traveled through an alley in the trees of the Sutro Forest, taking passengers to the front gates of the Ingleside track at Ashton Avenue. The earliest enterprises along Old Ocean Road were road houses patronized by gamblers.

“They had high hopes for it but it started as a strip with seven saloons,” said Woody LaBounty, co-founder of the Western Neighborhoods Project who is working on a book about the history of Ingleside Terraces. “It was a watering hole strip for the race track.”

That began to change after the racetrack closed and it was turned into a refugee camp after the 1906 earthquake. In 1910, the Urban Realty Improvement Co., led by Joseph Leonard, bought the race track land south of Ocean Avenue and developed the 148-acres while St. Francis Wood, Forest Hill and other subdivisions were being built. Developers wooed buyers with enticing newspaper ads and news copy gushed about fresh air, poppies and handsome, reasonably priced homes.

It’s easy to see why Levin saw the untapped potential. The commercial blocks closest to the theater were still mostly undeveloped when he initially approached Pflueger. Levin already operated several neighborhood theaters in the San Francisco Theatres Inc. chain, including the Coliseum, the Alexandria, the Harding, and the Metropolitan, with Michael A. Naify, vice president. Levin had also opened a theater, the first Balboa, on Ocean and Faxon in Westwood Park, not far from the proposed El Rey site, in December 1922, but it closed in 1932, after the El Rey opened.

In 1930, Levin and Naify decided to proceed with the project, which would include stores flanking the entrance to the theater. Even though the stock market had crashed, the boldest of theater operators saw a need for escapist, cheap entertainment. Pflueger and his firm were already working on the Paramount Theater in Oakland and they would soon be hired by the Nassers, who owned the Castro, to design a theater in downtown Alameda.

As a result, the design of these three theaters, especially their interiors, is in the same Moderne, now called Art Deco, style. The Paramount, a far larger theater originally designed with 3,600 seats, was on a grander scale since its client was the studio and theater operator, Paramount Publix. The materials used at the Paramount were slightly higher quality compared with the faux gold leaf used in detailing the bas reliefs and ornament on the walls of the Alameda and possibly the El Rey.

The 1931 opening of the El Rey was her- alded with big ads and news stories that de- scribed its “magnificent tower.” The stepped tower was topped with a flaring beacon, a built-in klieg light announcing the theater’s presence but technically was designed to warn airplanes of the tower in the often fog- shrouded neighborhood. The San Francisco Examiner described the tower as “sentinel-like in the midst of a new business block,” and said it was “destined to become a landmark by day and beacon star by night.”

In one of the few descriptions of the interior, the Chronicle described the lobby as “richly-toned in black and gold, with a complete gallery of mirrors extending the height of the side walls.” According to blueprints, Pflueger first drew a series of masks, likely to represent comedy and drama, to be cast in plaster bas reliefs on the auditorium sidewalls, but that idea was scratched. A small part of the audi- torium ceiling is still today covered with lace-like metal fins used more liberally and artistically at the Paramount.

Two grand staircases led from the lobby to the mezzanine, where patrons found a smoking room and other conveniences.

A rare photo of the interior taken in 1947 from the collection of theater historian and author Jack Tillmany shows a mural on the wall of the smoking room and specially designed angular, plush furniture. An even larger mural depicting modern transportation modes, a popular theme in the 1930s, graced another wall, according to collector Mark Santamaria.

“It was beautiful,” said Irene Kettler, 91, who worked as an usherette just after World War II. A long-time resident of Westwood Park, Kettler said in the 1940s and 1950s the neighborhood was like a small town. “We had a policeman who would walk up and down Ocean Avenue and usually they would come in to check if everything was all right, around closing time. On many, many nights I had a police officer walk me home.”

In the early days of the El Rey, the the- ater was home to the El Rey Food Shop, and a drug store. In the 1940s, a beauty shop and a dress shop occupied its retail spots. Photos from the 1940s show the base of the façade was originally faced in a dark flat stone, highlighted with horizontal strips of stainless steel or chrome. Above the marquee, an unusual pattern of concrete blocks formed patterns of diamonds and vertical zigzags.

John Pflueger, a nephew of Tim Pflueger, lived in Westwood Park before moving up to a house his father Milton designed on Robinhood Drive. He remembers Ocean Avenue and the El Rey in the late 1940s and early 1950s.

“My father took me to a movie every Friday night. We went to the El Rey all the time.” Pflueger, who is also an architect now in Sonoma, said he was too young to notice the architecture, but he remembered the El Rey as a better theater than the others he went to, including the Empire in West Portal and the Parkside on Taraval. “I was a kid just excited to go see a movie and get some popcorn and stuff.”

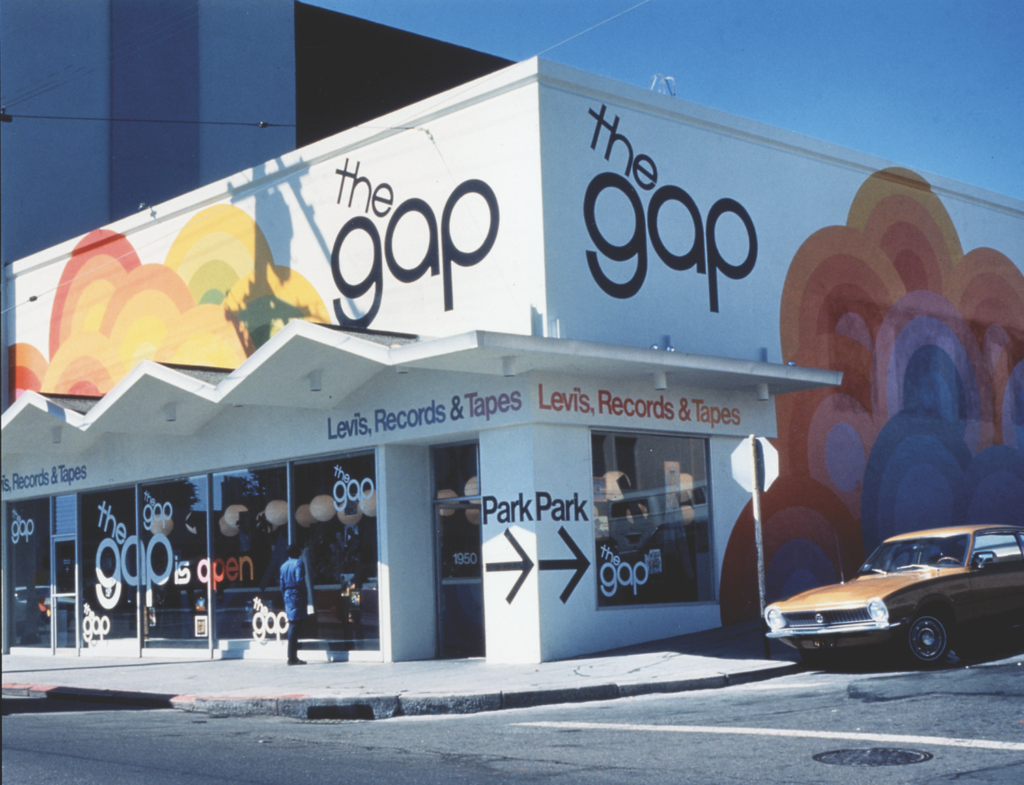

During the counterculture movement of the late 1960s, the first Gap store opened in El Rey’s retail space at Ocean and Fairfield Way, where inside the pop-painted storefront Doris and Don Fisher sold jeans and record albums. The neighborhood had started to change and at the same time, television was having an impact on movie theaters.

“I don’t think it was ever a premier retail strip,” said LaBounty. “I think the El Rey was a little over-optimistic.” After Stonestown opened in 1952, “it was a harder place to do business,” he added. After the war, some of the residential parks witnessed a flight to the suburbs that was also occurring across the U.S. In 1976, the Chronicle described Ocean Avenue as on the “brink of ragged change,” with a Safeway about to close. In a return to the area’s saloon roots, there were “eight stripped-down liquor stores” over eight blocks. “There are empty parking places in front of older stores and only a handful of shoppers at noon,” the Chronicle reported.

According to Tillmany, the owners of the theater, then known as UA California Theaters, closed the theater in 1976, but “some fast talking entrepreneurs convinced them that its future was as a revival house” and UACT reopened the El Rey, after a $10,000 rehab. “The results were to- tal disaster,” Tillmany said in an email. “The films they selected didn’t draw flies, and a dozen cus- tomers sitting in the vast expanses of mighty El Rey looked like lost children.” One film Tillmany saw in its last year was “Murders in the Zoo.”

The theater closed a year later. Its last hurrah as a theater appears to have been as host of a four-day Hookers Film Festival at the end of March, 1977 for COYOTE, the prostitutes’ rights organization founded by Margo St. James. That year, Marilyn Gazowsky, the founder of the Voice of Pentecost church who lives nearby, saw on the marquee that the theater was for sale. She believes she prevailed as the buyer because she was the only bidder who managed to get in touch with the owners.

“The young fellows who put it up there mixed up two of the numbers,” said Gazowsky, now 90, who still teaches at the Voice of Pentecost Academy once a week. “So United Artists never got a call. When my real estate man called, that was the first call.” Her church was only 11 years old at the time, but she had saved enough for a down payment on the bargain price of $365,000. The church holds services in the El Rey today, having done significant remodeling, with Gazowsky’s son Richard now its pastor.

Later this month, the church will convert once more to a theater on the evening of November 19, to celebrate its anniversary with a fundraiser for the Geneva Car Barn and Powerhouse. The Academy Award-nominated film, “The Smiling Lieutenant,” shown as the main feature at the gala opening in 1931, will be seen again in the theater’s auditorium. Eighty years later, the reinvented El Rey is a survivor in changing times.

Therese Poletti is a San Francisco based journalist and author of Art Deco San Francisco: The Architecture of Timothy Pflueger, published by Princeton Architectural Press.

No media outlet covers our neighborhood like The Ingleside Light. Full stop.

Reader support sustains the expensive reporting our community needs and deserves. Will you join the hundreds of readers and become a member?

We deliver neighborhood news, events and more every Thursday.