🟧 Jerry Garcia Street // Bookstore Annex Annihilation

In this week’s newsletter, we have the scoop on the latest Jerry Garcia commemoration plans and more.

The growing collage married to a handsome building is nothing without the community that Ingleside Presbyterian Church serves every day.

This June, Ingleside Presbyterian Chuch turns 117 years old. And Rev. Roland Gordon will mark his 46th anniversary at the helm in July. Last year, he received a Bay Area Jefferson Award and the Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis Award for extraordinary service to local communities. The Ingleside Light is republishing historian Woody LaBounty's 2011 column about the historic church and Roland's masterwork the “Great Cloud of Witnesses.”

By Woody LaBounty

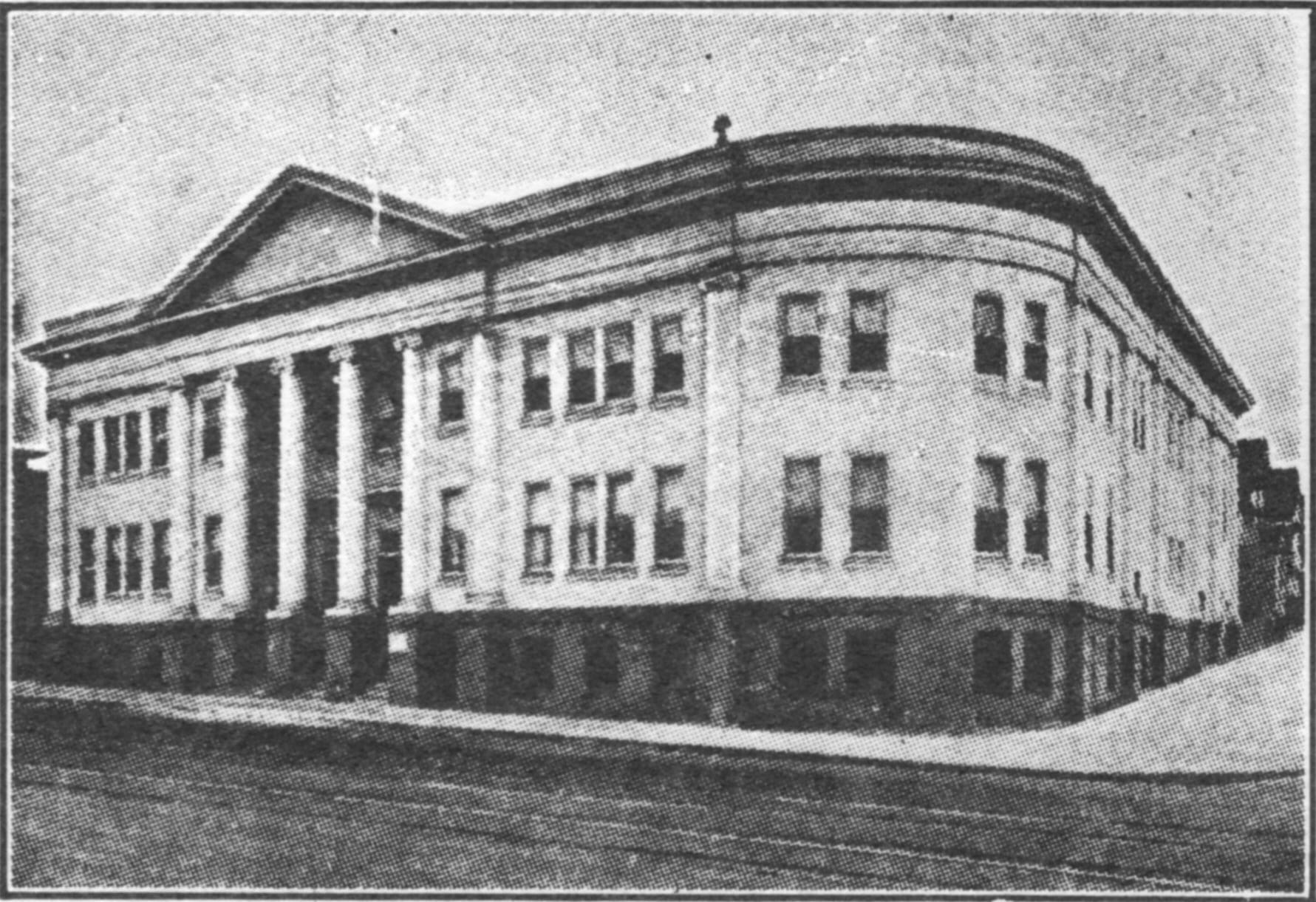

Ingleside Presbyterian Church is a great gray monolith, its entry framed by massive columns and a triangular pediment. Resembling a Greek temple (albeit with double-hung windows) the church has been one of Ocean Avenue's notable buildings since it was erected on the corner of Granada Avenue in 1923. But while the exterior architecture is striking, the church is more a San Francisco landmark for what's inside the walls.

Ingleside’s first places of worship were founded in the aftermath of the 1906 Earthquake and Fire, seeded by refugees encamped on the old Ingleside Racetrack grounds (now Ingleside Terraces). The name of St. Emydius Catholic Church calls back to these refugee beginnings, Emydius being the patron saint of earthquake survivors. Nearby, a United Presbyterian Church originated from a Sabbath School run in the basement of the Robinson Apartments (still standing at Faxon and DeMontfort avenues). In 1909, this Presbyterian congregation broke ground for a church building on the corner of Granada and Ocean avenues.

In 1920, the United Presbyterian Church was destroyed in an accidental fire, and rather than simply rebuild, local Protestants came up with an expansion plan. The UPC board of directors put up $25,000 to be matched by the community to fund a multi-congregational church and social service center. Joseph Leonard, who had developed Ingleside Terraces and designed hundreds of Bay Area homes, acted as the architect for the new place of worship. The grand building that now houses Ingleside Presbyterian was originally named “Ingleside Community Church,” and was home to nine different congregations, including Methodists, Baptists, Presbyterians, Episcopalians and Quakers. The San Francisco Examiner called it “a church that knows no differences in creed.”

More than a church, the new edifice included a community center with a gymnasium, three assembly rooms, a ladies' club room and a boys’ activity room. Campfire Girls, Boy Scouts, neighborhood guilds, service groups and clubs all used the center for meetings and events. The community service function of the building was important enough that money for a pipe organ in the sacristy was instead sacrificed for gymnasium equipment.

Unfortunately, the splintered allegiances of nine congregations quickly put the Ingleside Community Church on rocky financial footing. Some of the denominations split off to build their own churches as improved public transportation and the rise of the personal automobile gave worshippers options to attend services farther away. The Great Depression of the 1930s made matters worse, and the Ingleside community depended on rotating ministries to continuously bail it out of financial trouble.

In 1940, a dedicated pastor was assigned, building debts were forgiven by the United Presbyterian Board of Missions, and what had now become Ingleside Presbyterian Church finally became self-supporting. Church attendance was high in the 1940s and 1950s, and the center expanded with a chapel and many internal renovations. The late 1950s and early 1960s saw Ingleside Presbyterian become a multiracial congregation as African-American families displaced from the redeveloped Western Addition began to move to the neighborhood.

Changes that transformed America’s urban environments in the late 1960s and early 1970s hit the Ingleside neighborhood hard. Many homeowners retreated to new suburbs and much of the Ingleside became a low-rent district managed by absentee landlords. The new population, including college students from San Francisco State University and City College of San Francisco, were more transient and less likely to join a local church. Ingleside Presbyterian tried to meet the needs of the multi-ethnic neighborhood by having co-pastors, one African-American and one white. The arrangement ended up dividing the church, which lost both pastors. To keep Sunday services going, visiting pastors were called in and paid for the service. By 1978, the congregation could count its membership on the fingers of one hand.

Ingleside Presbyterian turned a corner that year. A first-year seminary student named Roland Gordon was hired at $50 a week to preach on Sundays. “Reverend G” brought renewed enthusiasm and a sense of purpose to the congregation, and like the founders of Ingleside Community Church, he saw a great asset in the gymnasium. Basketball could draw in the boys who spent too much time in trouble out on the streets. To help inspire the African-American youth who came in to shoot hoops, Gordon pasted a photograph and magazine story about Muhammed Ali on the gym wall.

Ingleside Presbyterian Church's gymnasium is covered in a mural with a collage. | Woody LaBounty/Ingleside Light

Here is where Ingleside Presbyterian became a unique San Francisco landmark and Gordon was able to add “collage artist” to his resumé. The Muhammed Ali photo soon had company on the gym wall. Gordon put up articles and photos of other athletes, entertainers, politicians, public servants, educators and historical figures until the massive collage of inspirational faces reached the ceiling 30-feet up. In 1992, artists Susan Cervantes and Selma Brown were brought in to create a capping mural in the rafters. “The Great Cloud of Witnesses” highlighted local and national African-American pioneers and community leaders, and added a dignified and vibrant exclamation point to Gordon's work.

Seeing the space for the first time is to gasp in amazement. Former San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown called the collage Gordon's great legacy. It’s one of San Francisco's significant works of art. More people should know about it.

San Francisco is losing its African-American population. In 1970 blacks made up 13.4% of the city. By 2005 it was down to 6.5 percent, the largest drop in any United States city. The 2010 census will no doubt reveal even lower numbers. Beyond the artistic merit of Gordon's work, the collage and the Great Cloud of Witnesses is an astonishing and emotive documentation of a community. And it's still not finished. The collage continues to grow, expanding down church hallways. Gordon jokes that he's “doing Michelangelo” with the goal of covering every empty space. “All you'll see is faces everywhere.”

My great thanks for the research and writing of Merced Heights resident Steve Wolf in preparing this column.

We deliver neighborhood news, events and more every Thursday.