🟧 96 Units On Ocean // Balboa Reservoir Project Update

In this week’s newsletter, we dig into plans for 96 units of housing on Ocean Avenue and more.

Special streetcars played an important part in connecting city residents to burial grounds south of the city border.

This article is an installment from the Friends of the Geneva Office Building & Powerhouse’s new history email series, eight daily emails uncovering the Sign up for the history email series here.

San Francisco’s leaders had decided in 1890 that land was too valuable for use as burial grounds. So streetcars were needed to take people south to the cemeteries to pay their respects and attend funerals.

By 1902 United Railroads began operating its funeral parlor streetcar service out of the Geneva Car Barn. Local funeral parlors and the Cypress Lawn Cemetery Association in Colma were eager for the service since the condition of the unimproved roads was so bad. Also, since the San Francisco Board of Supervisor’s ordered the disinterment of bodies from all of the city’s graveyards in 1912 there would be no more cemeteries in San Francisco.

As new cemeteries were built there was an increased need for transportation to Colma’s necropolises. “Light rail” spurs (or tracks) were laid for the electric streetcars to have direct access into the memorial parks right off the San Mateo line.

Pictured: Cemetery Line Streetcar 1242 beside the Geneva Office Building with the Geneva Car Barn at back.

United Railroads began with one small vehicle — the “Cypress Lawn” — which originally had been motor-less and needed to be towed. For their second, United Railroads converted one of their St. Louis Car Company passenger cars into a very fancy funeral parlor car. Between 1903 and 1904 three more finely appointed vehicles were added to the fleet. These three new vehicles were built in-house at the 28th and Valencia shops. They followed the 14 Mission and 40 San Mateo routes to Colma by way of Mission Street, El Camino, and Mission Road.

The funeral parlor cars were painted Brewster Green with tile-red roofs, gold lettering, and golden oak window sashes. Each had separate compartments for the coffin, the family, and friends. Some had lead inserts in the gears and wheels to make for a quieter ride. United Railroads promised “elegantly equipped cars … quick service, privacy and courtesy assured.”

Pictured: The interior view from the casket area, one can see the wood-paneled pocket doors and through to the mourners’ section.

Accidents happen. But an accident on the “cemeteries” line is a tough story to think about. Pictured: Cemetery Streetcar 1240 after accident, at Geneva Car Barn, January 11, 1916.

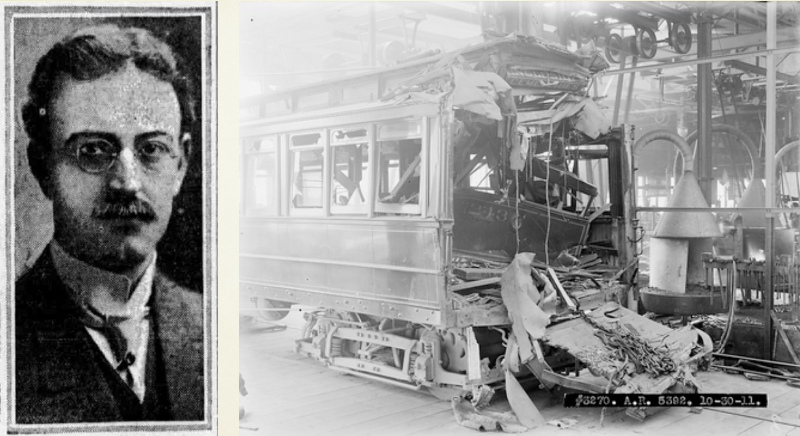

Pictured at right: A damaged car taken after an accident on the “cemeteries” line is especially hard to look at. While it is not the vehicle which struck and killed Eminel P. Halsted, pictured at left, it could have been. This story is particularly sobering because Mr. Halsted was an undertaker with Halsted Brothers. He was returning from a funeral at which he had just officiated on December 9, 1916. He stepped out of the hearse to cross the tracks to visit the Weisenberger Marble Works. There were two cars approaching with speed — one outbound and one inbound. He was struck by the inbound car and taken, in his hearse, to St. Luke’s Hospital where he died. He had lived with his family in their beautiful two-year-old home at 178 Sea Cliff Ave. in San Francisco. His widow Clara Brown Halsted and their nine-year-old son survived him.

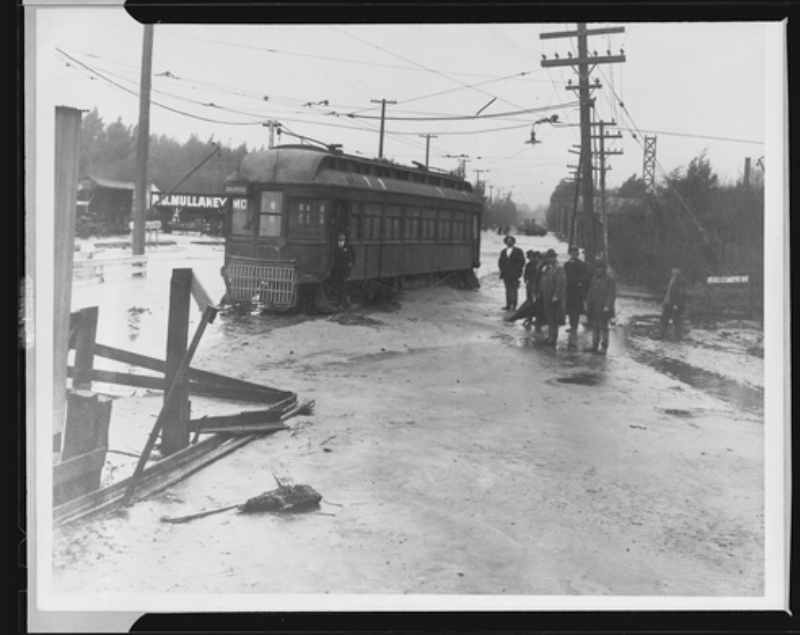

In addition to accidents, winter floods could make travel by electric streetcar dangerous if not impossible. As roads were paved and improved, automobiles became ubiquitous. Eventually the service to the graveyards became unprofitable and United Railroads suspended it.

The Geneva Car Barn was the headquarters for this special funeral parlor car service as early as 1902. By 1908 United Railroads began decreasing the number of vehicles in its fleet. The three cars built at the 28th and Valencia shops were the last ones in operation — and the final day of the funeral streetcar service in San Francisco was March 24, 1916. By 1926 the remaining vehicles had been scrapped and sent to the Elkton Shops where their trucks, motors, and controls were salvaged. Their recycled parts lived on in passenger cars for many years.

This article was created by Friends of the Geneva Office Building & Powerhouse board member Lisa Dunseth. View a detailed slideshow version here. If you can, please consider making a tax-deductible donation to support the publication of the book.

This story you’ve just finished was funded by our readers. We want it to inspire you to either sign up to become a member or make a gift to The Ingleside Light so that we can continue publishing stories like this one that matter to our community and city.

The Ingleside Light is a reader-funded news publication that produces independent journalism to benefit the community. We were founded in 2008 to fill a void in San Francisco’s press: An outlet dedicated to the people of the greater Ingleside neighborhood. More than a decade later, The Ingleside Light is still here doing the work because it is critical to democracy and our civic life.

Your contribution today will help ensure that our critical work continues. From development to small business, to parks and transportation and much more, we are busier than ever covering stories you won’t see anywhere else. Make your gift of any amount today and join the hundreds of readers just like you standing up for the power of independent news. Thank you.

We deliver neighborhood news, events and more every Thursday.