🟧 96 Units On Ocean // Balboa Reservoir Project Update

In this week’s newsletter, we dig into plans for 96 units of housing on Ocean Avenue and more.

A look back at this history of the neighborhoods through the life and times of the late Valente Marini Perata Mortuary.

History is a conversation with the past.

BRIDGE Housing is building 137 affordable rental apartments at 4840 Mission St. on the former site of the Valente Marini Perata Mortuary. The complex will include a pedestrian walkway connecting Mission Street to Alemany Boulevard featuring informational panels and an historic timeline.

I was pleased to be asked by BRIDGE staff to help with their history panels, after all, I am one of those people who actually reads such things.

Below you'll find my version of the panels with regard to the Italians in the Excelsior, the surrounding groundwater and the mortuary itself.

I hope it inspires you to walk around with your eyes open to the past. If you peel back the layers, even just a bit, you will be surprised. You'll find a deeper appreciation of your neighborhood and catch a glimpse of how people lived then.

We invite you to join the conversation by sharing your thoughts and memories about the evolution of this place known as the Excelsior and Outer Mission.

The Ohlone people lived in this expansive valley before it was included in José Cornelio Bernal's 4,400-acre Mexican land grant in 1839. It was named the Rancho Rincón de las Salinas y Potrero Viejo or "ranch of the salt marsh and old pasture."

Walking paths in the district became horse and wagon trails and evolved into transit routes which could move people and goods from the Excelsior and the Outer Mission downtown and from the city center to points south. In the 1850s rails ran along San Jose Avenue. In the 1870s, the Southern Pacific Railroad ran freight and passengers along what is now the Interstate 280. From 1905 to 1921, the Ocean Shore Railroad ran along Alemany Boulevard. In 1894, the Market Street Railway ran a streetcar along Mission Street from the Ferry Building to Excelsior Avenue. Today's Mission 14 bus route was established in the 1920s.

This entire valley and surrounding hills, with its abundant groundwater and access to Islais Creek, began attracting immigrant farmers and dairymen in the 1860s. Large numbers of Italian, German, Swiss and Irish immigrants bought land to ranch and cultivate. Truck farmers leased land and took their produce by horse and wagon downtown to sell.

1. One of the remaining buildings from José Cornelio Bernal's 19th century rancho, located on west side of Alemany Boulevard near Ocean Avenue in 1925. Credit: UC Berkeley Bancroft Library 2. Ocean Shore Railway's Mission Viaduct in 1915. Credit: OpenSFHistory. 3. Kate Mitchell with dairy cows on Munich Street in late 1890s. | San Francisco Public Library History Center

Italians came here, like so many others, for the gold rush of the 1850s. In the 1860s, farmers from Liguria, Tuscany, and other parts of Italy populated what would eventually be named the Excelsior District. Italian-Swiss dairymen arrived too and they all took their produce by wagon downtown to sell at market. As late as 1910 1,200 Italian giardinieri (truck farmers) worked some 8,000 acres on San Francisco's south side.

The events of 1906 forced San Franciscans out of the ruined city center and south to rebuild their lives. The Excelsior offered a place to build an affordable home with a garden and open space for their families. By 1930 the area was well developed with one-story-over-garage single-family homes next to older farm houses and cottages.

The Italians worshipped at Corpus Christi Catholic Church, founded in 1898, and later the Church of the Epiphany. The Feast of the Madonna della Guardia was celebrated with a procession down the middle of Mission Street. They banked at A.P. Giannini's Bank of Italy which opened its first branch in the Excelsior (later renamed the Bank of America.) They played bocce ball on neighborhood courts. They played baseball too — like Rinaldo "Rugger" Ardizoia who went on to play professionally. And they boxed as well, like Ray Actis who was known as the "Excelsior Assassin."

Italian businesses, like Ferrera Hardware (1914-1992) and the Royal Baking Company along with numerous macaroni and pasta factories, flanked Mission Street in the years between the world wars.

Rita Conte Gelini remembers many small businesses from the 1950s. She describes the Excelsior of her childhood as a "self contained community." There was everything anyone needed: markets, delis, restaurants, bakeries, bars, barbers, beauty shops, pharmacies; stores for shoes, clothing, jewelry, hardware; offices for dentists, doctors, attorneys, insurance, real estate; and even a music school.

Mission Street was lined with places like Joe’s Fish Grotto; Mario Bruzzone Market (later John Zuffi's); Rocco’s Restaurant; Excelsior Poultry (and fish); Aida chocolate factory; Red Cherry Bakery; a German delicatessen; Marcon Shop and Pardini’s (clothing); Farrah’s (shoes and clothing—owned by a Lebanese American family); the Granada Theatre (owned by a Lebanese American family); Siri’s laundry; Sorrento’s (now Calabria Brothers); Pezzolo's (accordion music school); Cresta Brothers Auto Parts; Borelli Hardware and Bike shop; Jebe Camera Shop; Central Drugstore (still in business); Granada Cafe (where the card game Pedro was played); and Fregosi Florist (next door to Valente, Marini, Perata.)

The business owners were involved in the community and advertised in the Balboa High School yearbook. The Excelsior Merchants decorated Mission Street for the holidays and hosted Christmas parties for children. Kids, independently and at a relatively young age, learned to shop at Woolworth's, the Hobby Shop and the Granada movie theater by themselves.

The Italian American Social Club (where the Northern California Veteran Boxers Association still meets today) and the Sons of Italy (opened in 1957) anchored the corridor where Italian families remained the dominant group into the 1960s.

By the 1970s as the Italians began leaving for the suburbs new waves of immigrants arrived from Mexico, Central America and the Philippines until they became the dominant demographic. Today, in 2022, the Asian population predominates the Excelsior and Outer Mission.

The presence of abundant groundwater and Islais Creek made it possible for farmers and ranchers to settle this area. The Italian farmers in Spanish-influenced Genoese referred to this low-lying riparian plain, which followed along the ridge of Alemany Boulevard, as a "cagnada rica" or rich ravine. There was also a large Chinese vegetable farm, specializing in cabbage, where Balboa High School now stands.

People dug wells and used the creek in various ways. One of the original late 19th century "Mile Houses" is believed to have been located at 4716-4722 Mission Street (between Ruth and Leo streets) and Mary Ellen Pleasant owned a ranch near San Jose and Geneva avenues around the same time. Both would have needed water.

A French family owned Hayes Park Laundry, built in 1890, which operated at 915 Cayuga and freely used the waters of Islais Creek for almost 100 years. As early as 1910 there were lawsuits regarding the use and abuse of this water — suits filed against the city and suits filed by the city.

Private wells were used for everyday cooking and irrigation of gardens and fields but there were also beer and soda pop businesses nearby. Blue Crest Beverage Company (later Mission Beverage) was located at 615 Excelsior Ave. and 285 Naples St. The Eagle Brewery, otherwise known as the Golden Eagle and El Rey, operated at 5050 Mission from 1912 through the early 1940s.

Today it is not unusual for construction workers to encounter water as they dig. And Balboa High School's lower level still floods occasionally.

Weddings and funerals are two of the most significant occasions for most people. For the Italians in the Excelsior the Valente, Marini, Perata & Co. Funeral Directors served the community's mortuary needs for over ninety years before it closed in 2017.

Virgil Valente, Frank Marini and John B. Perata and their families had managed mortuaries since 1888. Their original location on Stockton Street was destroyed in 1906. Marini, who became a prominent philanthropist and community leader was known as the "Mayor of North Beach." He is credited with burying the firm's ledgers and records as the fire approached which enabled them to resume business soon after the disaster. In 1907 their new building at 649 Green St. opened for business in North Beach.

1. Frank Marini (1862-1952) the "Mayor of North Beach." Credit: Find A Grave 2. Advertisement, San Francisco City Directory, 1925. | San Francisco Public Library History Center

They opened the mortuary at 4840 Mission St. in 1926 — after temporarily working out of a storefront at 3448 Mission St. — to meet the demands of the Excelsior's growing population. Herb Caen once wrote that Valente, Marini, Perata had "handled every big Italian funeral since 1892."

The building may be gone but it is remembered by many since it played a significant role in the community well into the 21st century. May this new affordable housing complex serve the needs of the community as well.

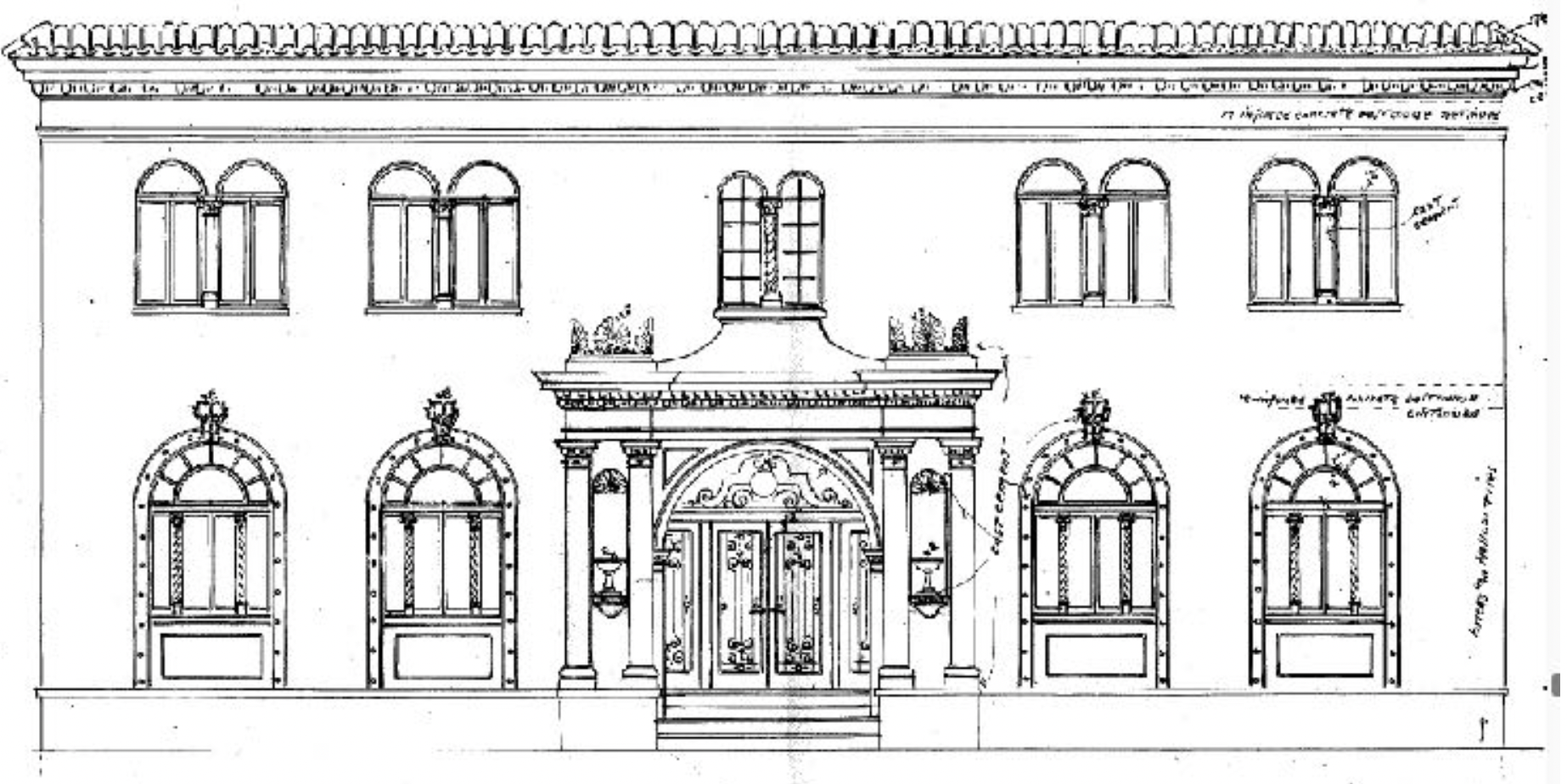

The original building at 4840 Mission St. was designed by John A. Porporato (1877-1965) a San Francisco native and prominent Italian-(Piedmontese)-American architect. He was married to Mary Porporato and they had two children, Albert and Anita (De Vincenzi.) Porporato's funeral was held at the Valente, Marini, Perata Green Street location and was followed by a high mass at Saints Peter and Paul Church — a structure he himself had completed after the original

architect died.

1. Portrait of John Porporato from the 1936 Italian Athletic Club dedication pamphlet. 2. Aerial view showing gardens from 1938. | David Rumsey Map Collection

Porporato apprenticed in the offices of Maxwell & Bugbee and eventually opened his own office at 619 Washington St. He was a prolific designer of apartment buildings in San Francisco in the early twentieth century. One of his most notable buildings was the San Francisco Athletic Club on Washington Square (now the San Francisco Italian Athletic Club.)

A partial list of his work includes: apartment buildings at 972-976 Pine St.; Clay between Powell and Mason; southwest corner of Franklin and Francisco; southwest corner of Polk and Greenwich; and southeast corner of Greenwich and Stockton; a chapel for the Società Italiana di Mutua Beneficenza at the Italian Cemetery; the Salesian House of Studies in San Pablo; and the Porporato Garage at 4434 Mission St.

Permits were filed on Dec. 17, 1925 for a two-story brick mortuary to be built at 4840 Mission St. at a cost of $40,000. Construction began in 1926 and was finished within the year.

It was built in the Spanish Colonial Revival style with stucco exterior, red tile roof, and pairs of arched wood windows which elegantly lined the façade. The Mission Street side featured a central entry portico, vertical bays of arched windows, wood entry doors, a projecting canopy, a porte-cochère and stucco scored to resemble ashlar masonry.

At the rear, the building stepped down to a single story and then stepped up again to a single story over a raised basement with roll-up garage doors. The building included a formal landscaped garden along its Alemany side (demolished in 1956.)

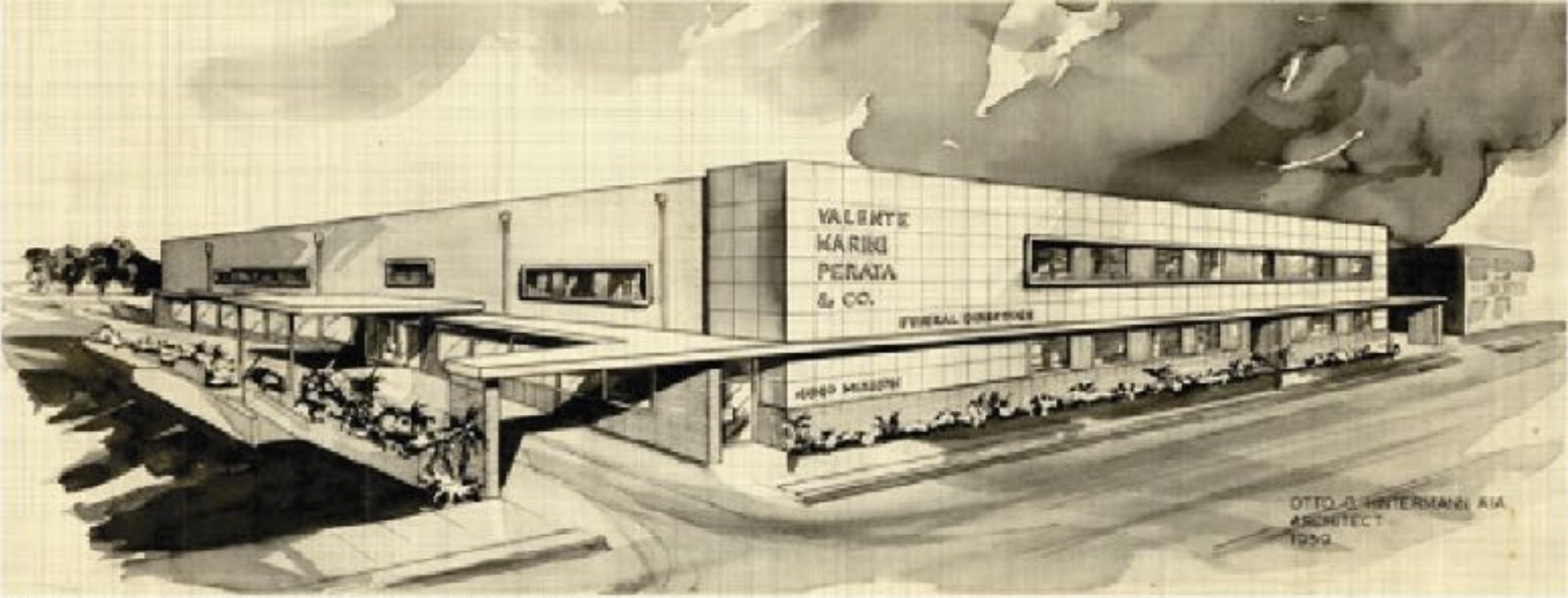

In 1959 architect Otto G. Hintermann was hired to remodel the building and design a large addition at an estimated cost of $185,000. Today Hintermann is not regarded as a master architect. He was active in local architecture groups in the 1930s but was better known for his volunteer work as a World War I veteran and commander of the San Francisco Post of the American Legion. He was described as “one of the most popular veterans in San Francisco” and helped organize the Veteran’s Fete to mark the 20th anniversary of World War I. He was married to Marguerite Hinterman whose funeral was held at 4840 Mission in 1954. He later

married Cleo Vreeland whose funeral was also held at 4840 Mission in 1977.

Hinterman was hired to design in the popular Midcentury Modern style. The exterior ornamentation on the east and south sides of the original building were removed and the structure was extended to the south, east, and west with a two-story addition.

The building was expanded to include four chapels, three reception salons, two apartments on the second story for staff, a casket showroom, and embalming facilities in the basement. Since the building had remained substantially unaltered since 1959, the Hinterman building was an important intact example of a large-scale Midcentury Modern commercial building in San Francisco.

On the east side along Mission the window openings were altered and porcelain enamel panels and roman brick veneer were placed across the entire façade. Other defining features included clean lines, a flat roof, aluminum sash windows and doors, minimal exterior detail, and projecting boxes to frame the windows at the second story.

Selected images of the funeral home. | San Francisco Planning Department

The prominent signage, both neon and painted, were designed to be read by drivers traveling up and down Mission Street and Alemany Boulevard. There were three neon signs on the property: one large sign on Mission included the word "parking" was added in 1937 and one on Alemany was added in 1961. There was also a mid-sized sign projecting from the building over the Mission Street sidewalk—this one was saved from demolition and is being restored.

There are still quite a few Midcentury Modern buildings along Mission Street. They include: Central Drug Store, 4494 Mission (1910 but altered ca. 1950); 4680-4690 Mission, architect Mario Ciampi (1949); Granada Cafe, 4753-4757 Mission (1949); Sons of Italy, 5051 Mission (1952); Mission-Serra Motel, 5630-5638 Mission (ca. 1955); Woolworth Building, 5825-5845 Mission (1956); commercial building, 5200-5210 Mission (ca. 1970); commercial building, 4650 Mission, architect Mario Ciampi (1950); commercial building, 8 Persia, architect Mario Ciampi (1953); Corpus Christi Church, 62-64 Santa Rosa, architect Mario Ciampi (1952); and the Cresta Brothers Auto Parts, 5050 Mission, architect Mario Ciampi (1948) demolished and replaced with new housing in 2017.

Correction: The ownership of the Granada Theatre has been updated.

We deliver neighborhood news, events and more every Thursday.